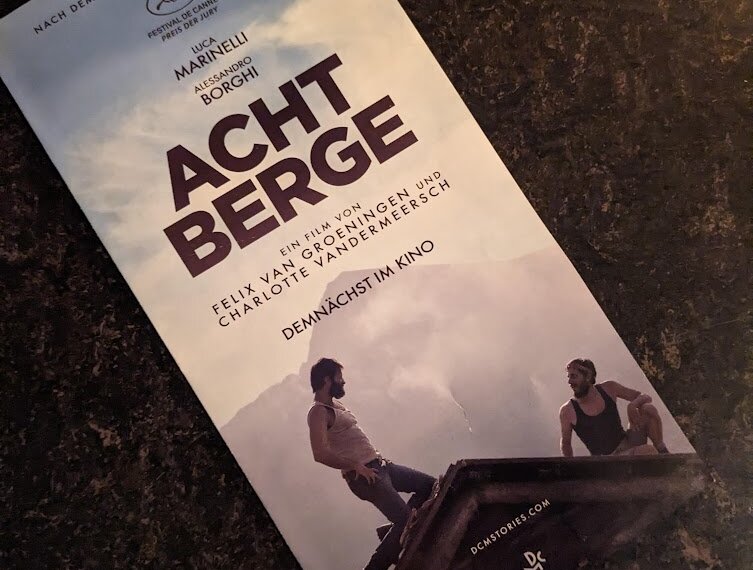

“The Eight Mountains” tells the story of unusual people who decide against modern city life and those who don’t, raising the question to which extent we follow other people’s dreams instead of our own. Another film covers similar topics: erzählt die Geschichte ungewöhnlicher Menschen, die sich bewusst gegen das moderne Stadtleben entscheiden oder eben nicht, und stellen die Frage, wie sehr wir unsere eigenen Träume oder die anderer verfolgen. Auch ein anderer Film befasst sich mit ähnlichen Dingen. Anstelle beeindruckender Landschaftspanoramas werde bei “Was man von hier aus sehen kann” (“What can be seen from here”) celebrates bizarre details of a village community that seems to have fallen out of time, but I can confirm that I have been to similar places not far from the place that I grew up. The Okapi omen is the only unrealistic aspect of the book, and the film is great but it fails to include subtle detail that the grandmother was supposed to “look like Rudi Carrell”, one of the male entertainers of the 1980s who cared much more about an elegant outfit and hairstyle than men were supposed to do traditionally.

Back to the title story: the father-son-relationship, the unrecognized dreams, and the feigned freedom of tourism reminded me of my own youth, and of an affectionately satirical book, “Vorzelt zu Hölle” (“Awning to Hell”) written by Tommy Kreppweis together with his father, looking back on camping tours they did as a family.

I also have to think of modern “glamping” which often looks more like mass tourism on a truck car park than the idyllic scene of a tent or a campervan outdoors in the wilderness. Long ago, in the days before the internet, we used to travel spontaneously without making a reservation. These days, it’s crowded everywhere, packed with gigantic grey mobile homes. My father loved road movies, so he used to turn a minibus into a campervan and drove us to Europe’s North Cape and to southern Greece. I got bored on the long read trips and failed to empathize his joy of driving. Later, in the driver seat of a Volkswagen campervan, I started to sense some of his fascination, but I also felt that I needed to distance myself and mock the camping lifestyle to break free from the feeling of chasing somebody else’s dreams. On other trips I proved that it’s even possible to go far without cars and planes by focusing on biking, hiking and train travel, at least if you are willing and able to spend more time and money.

But no matter how far and by which means I travel: I always take my personal history with me. So a critical analysis of one’s past might help to find happiness and prevent passing misfortune and unhappiness to the next generations.

At a conference, Tobias Baldauf surprised the audience with a very personal talk. You can watch his talk on YouTube: www.youtube.com/watch?v=JGiyec5b5xU. A related item my stack of unread books: “Kriegsenkel” (“Grandchildren of War”) by Sabine Bode.

A hopeful, romantic, sarcastic, and funny book that I already read, features parallel worlds and seemingly missed chances:

Schon gelesen habe ich ein hoffnungsvoll romatisches, sarkastisches und lustiges Buch über Parallelwelten und vermeintlich verpasste Chancen: The Midnight Library by Matt Haig.

Final thoughts: it would be unreasonably selfish and self-pitying to focus too much on one’s past. On a thoughtful train trip to the past (family home, class reunion, sick call) I overheard a young father reading to his children from a book by Astrid Lindgren, cited analogously from “Karlsson on the Roof”:

Lillebor asked himself if he is also “a man in his best years”, so he asked “which are the best years?” and Karlsson replied: “all of them!” What a happy ending taking me back to the present times!